Worm Infestations in Fish

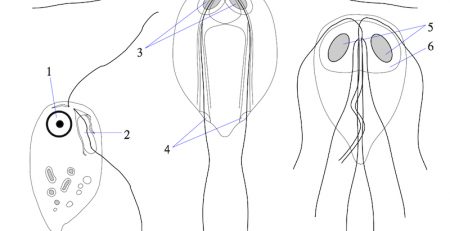

As anyone who has tried to maintain a fresh or saltwater aquarium is certainly aware, fish in captivity are subject to a myriad of health problems. In addition to the often discussed external pathogens, such as protozoa, bacteria, trematodes, etc, fish may also host internal infestation of parasites. One group of parasites that may cause problems in fish is the worms. These include the roundworms (nematodes), tapeworms (cestodes), thorny-headed worms (acanthocephalans), and flukes (digeneans). Most of these worms do not pose a serious health risk to the fish because they often have complicated life cycles in which the fish may serve as only one of possibly several intermediate hosts. A fish with internal worms may appear completely healthy, exhibiting no symptoms of infestation. Nematodes in the body musculature for instance, do not impair a fish’s maneuverability when they are present in small numbers. (They may, however, prove unsightly and unappetizing to the fish market patron!). Another apparently benign association involves the flashlight fish. Most flashlight fish mortalities, upon necropsy (autopsy) are found to harbor a pair of digenetic trematodes in the gall bladder. This relationship has not been investigated, but the trematodes do not seem to cause the host any great harm.

Other worms can threaten a fish’s well being and do warrant treatment by the home aquarist. The challenge is diagnosis, not always a simple task. Juvenile and adult worms may be observed in the course of a necropsy, but ideally the aquarist would like to identify the problem before mortalities occur. Common sites of internal infestation include nematodes coiled in the mesenteries or musculature, cestodes in the gut or inside other organs, acanthocephalans in the gut or boring through the intestinal wall, and trematodes in the gut, organs, blood, gills, etc. After a problem has been identified through necropsy, the aquarist has to decide if the mortality was the only fish harboring worms of if all fish in the tank are infected. Considering the worms complicated life cycles, most infested fish must come in contact with the worms before they get into the pet trade. Since the necessary intermediate hosts are not usually found in the tank along with the fish, transmission of worms between fish within a hobbyist’s tank does not readily occur. If several fish of the same species were obtained as a group, it is usually assumed that the survivors are also carriers and they are treated accordingly.

The next most direct method of diagnosis, if observation of worms during a necropsy is not possible, is finding adult worms, larvae, or eggs in the feces. Microscopic examination of feces is not a routine procedure nor is it a very easy one. The aquarist may try this procedure if experience, through necropsies, has shown that a particular species typically has intestinal worms of if the individual fish exhibits external symptoms of infestation (discussed below). In order to secure a fecal sample, the fish is best kept in a scrupulously clean, bare-bottomed tank in order to see the dropped feces. Also, the fish must be eating and thus producing feces, and the aquarist must be very lucky to be looking in the right place at the right time. Not all fish produce pelleted feces and the waste material can break down fairly rapidly, so this technique may not always be possible.

A third method of diagnosing a problem with worms is indirect and, at best, just a guess. When a fish is eating well yet is still not putting on weight, and intestinal infestation may be suspected. This is particularly when a fish eats regularly yet actually looses weight, metabolizing body musculature to stay alive. This is usually seen as thinning along the back on either side of the dorsal fin. In an extreme case this may result in a well-fed fish starving to death.

Treatment of worms has not been well studied and medications and dosages must often be extrapolated from veterinarian practices. This can result in some rather broad generalizations and assumptions that are difficult to substantiate. The list of treatments discussed here is by no means exhaustive but merely some of the things tried at the John G. Shedd Aquarium in Chicago.

As with treatment of fish diseases, medications for treating worms can be administered in one of three forms: as a bath, in treated food, or by injection. Powdered medications or capsules can be dissolved and added directly to the tank. Dosages are often listed with parts per million (ppm) as the units. This is the same as milligrams per liter (mg/l), although this still may not be a convenient measurement for the hobbyist. A stock solution of medication can be prepared by dissolving 75 grams (g) active ingredient in one liter (L) of water. One drop of this solution in a gallon will yield one ppm. As an example, to treat a 50 gallon tank at 25 ppm (with a solution that produces one ppm at one drop per gallon) requires 50 gallons x 25ppm= 1.250 drops. Don’t panic! it is not necessary to count drops all day long. Twenty drops equals one milliliter (ml), so 1,250 drops/20 =62.5 mL = approximately 12.5 teaspoons (tsp.).

If the fish to be treated is eating well, it is often easier to medicate the food. For large fish this may simply require slipping a tablet or a gelatin capsule containing the medication into a piece of cut food , such as smelt tail. Deworming medications often do not well in water, but a suspension can sometimes be injected with a hypodermic needle into a piece of cut food. For dosing one ml. of the stock solution mentioned above contains 75 mg of active ingredient.

Medications can also be applied to pellets or ground food. The proper amount of medication can be mixed with the water and the pellets soaked in the solution. This dosing is not precise, but at least some medication makes its way into the animals. With practice, the amount of water used to prepare the suspension can be reduced to just enough to be completely absorbed by the pellets. A common rule of thumb is that a healthy fish eats 3% of its body weight per day, so that quantity of food will have to contain the prescribed dose for that fish. Dosages are often listed as milligram per kilogram (mg/kg) body weight. One way to estimate the weight of a fish is to consider how its size compares with that of a quarter pound hamburger (precooked weight). a quarter pound is about 100g (= 0.10kg). Mixing the medication with pellets or ground food allows for easier treatment of many fish at a time. That way individual capsules do not have to be weighed for each patient. This technique of soaking the food in medication does not work well with flaked food.

As a last resort, at the Shedd Aquarium, we may force feed a fish that refused to eat, for whatever reason, and is in danger of starvation. This requires anaesthetizing the fish, putting a tube down its throat and pumping in a slurry of food and medication with a syringe and catheter tube. The material and expertise required for force feeding generally precludes its use by the home aquarist.

Medications

Several medications have been tried with varying results. Praziquantel (for example, Droncit) is routinely used orally as a canine and feline dewormers. It has also been used as a bath against monogenetic trematodes in fish.

( Note from webmaster: I received an email saying that the dosage listed below is not correct and should be approximately 2 mg/L. In going through some of my other issues I see that there is another article in the fall 89 issue of SeaScope that lists an update to Praziquantel. Please use caution when using information from these articles. I put them up for reference information to try and help people out. But I cannot verify accuracy or information provided. SeaScope is still putting out this newsletter 12 years after this article was published so I presume they generally are fairly reliable. But obviously there can be mistakes.

The dose is 250mg/L added once to the tank and left in for three days. It has been suggested that Praziquantel in water may make its way into the bloodstream across the gills but this has not been proven and does not appear to be a very efficient way of treating internal problems.

Oral dewormers include Praziquantel, piperazine (for example, Pipfuge) and fenbendazole (for example, Panacur). Again, each is commonly used in veterinarian work. The dosage rate for Praziquantel in canines is one half of a 34 mg tablet for dogs under 10kg and one 34 mg tablet for dogs up to 20kg. Such a wide range suggests this treatment is best used on large fish (one kg and larger) to avoid overdosing. In establishing the dosage, researchers probably did not consider treating 110g or smaller animals, (a more realistic weight for aquarium fish!). Praziquantel is easy to dose and is fairly easy to administer in large fish. We have had good success with embedding half of a tablet in a piece of cut smelt and offering it to the infested fish.

Fenbendazole is used in horses against roundworms. A typical recommendation is one 5g packet/500 lb. horse. A difficult question to answer is how many angelfish make up one horse-equivalent. This borders on the ridiculous when trying to weigh out medication for one fish. This treatment would be much more practically administered mixed in a large batch of treated food distributed to several fish.

Praziquantel is available as an injectable medication , but we at the Shedd Aquarium have had no experience using this form against worms.

The treatment of internal worms in fish is not an exact science. Most of the medications were not developed specifically for fish nor has their application to fish hosts been well studied. However, when even circumstantial evidence indicates a worm infestation, the hobbyist does have some treatment options. The protocols mentioned here may be worth experimenting with using the above mentioned medications or with other drugs as they become available.

Editors Note:

Based on hatchery experience, use of gelatin based foods for administering medications is a practical method. Spotte (1973) outlined a simple diet, in Marine Aquarium Keeping, which could be supplemented with one of the suggested medications.

Also , a small 4 ounce (112g) batch of food could be easily made by making a 3 oz (85g) puree’ of shrimp tails (NO HEADS) in a blender and adding enough water and medication to come up to 4 oz (114g). Gently warm to about 120 degree’s F (49 degree’s C) and slowly blend in about 1-1/2 tsp (8-9g) plain gelatin (such as Knox) until smooth. Refrigerate, or freeze if it will not be used with 2 days. This blend makes about 122g of food and there are any number of variations on this theme, such as using fish, clams, algae, etc.

Regarding dosing of medications, if the authors 3% body weight per day is used as a feeding guide, then a 1kg fish would eat 30 g of food. So the daily dosage in milligrams of medication per kg of animal would have to be in the 30g of food. Thus, the 120g batch would need 4 times the recommended daily dose.

Example: From the text above, the suggestion is one 34mg tablet Praziquantel for up to 20kg or 1.7 mg Praziquantel/kg body weight. We would want this 1.7mg in 30 g of food so we could need 1.7×4=6.8mg in the 120g batch of gelatin food. To make the diet about 1/5 of a tablet would need to be crushed and powderized and then blended into the food before chilling. This procedure could be used equally well for other treatments, such as oral antibiotics and vitamins. It would be wise to check with your veterinarian or pharmacist to be sure of proper dosing. Caution should also be exercised to avoid overfeeding.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.